Text Formatting

These first few chapters discussed very much the global workings and overall concepts in LaTeX. How to approach a new document, how to structure a project for success, etcetera. Now it’s finally time to look at the small details—formatting the actual words, sentences and paragraphs.

LaTeX performs a lot of guesswork. It uses a set of typographic rules to guess what you wanted to say with your markup and determine the best layout. For example, by default:

- Text is justified, which means spacing between words is slightly adjusted to make every sentence the exact same width. If LaTeX has to adjust word spacing too much, it will give a warning, but still compile correctly. If a line has too few words, it’s an underfull box, if it has too many, it’s an overfull box.

- As another way to accomplish this, words at the end of the sentence are sometimes split into two. LaTeX, most of the time, knows where it can do this, and adds hyphens.

- Orphans and widows are prevented. This means that it tries to never end or start a page with a single line, but keep paragraphs together.

Most of the times, LaTeX is right and everything looks great 😃

Sometimes you need something different or it doesn’t work out. That’s when you can override and change this behaviour.

New Lines & Pages

By default, when you leave a blank line in your document, LaTeX starts new paragraph. It indents the next line, without leaving vertical white space between the two paragraphs. If you don’t want that many empty lines in your document, you can do the same with the \par command.

Sometimes you might want to force a new line, without starting a new paragraph. This is done with \ or \newline.

The star variation, \*, prohibits a page break after the line break.

To start a new page (“hard return”), use \newpage.

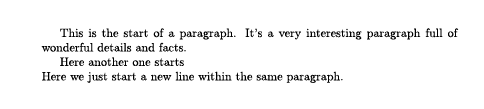

1This is the start of a paragraph. It's a very interesting paragraph full of wonderful details and facts.

2\par Here another one starts

3\ Here we just start a new line within the same paragraph.

Instead of forcing breaks, you can also suggest LaTeX use them. The compiler then decides for itself when it’s best to follow or ignore your suggestions. For this, use these commands that suggest to (not) add a break:

1\linebreak[n] \nolinebreak[n] \pagebreak[n] \nopagebreak[n]Here, the argument n can be a number between 0 and 4. The latter (4) forces LaTeX to follow your suggestion, and the first (0) leaves it completely optional.

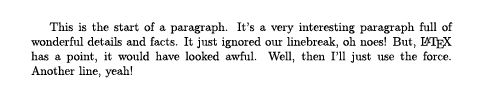

1This is the start of a paragraph. It's a very interesting paragraph full of wonderful details and facts.

2\linebreak[2] It just ignored our linebreak, oh noes! But, \LaTeX{} has a point, it would have looked awful. Well, then I'll just use the force.

3\linebreak[4] Another line, yeah!

Hyphenation

By setting a language for your document—which you’ll learn soon—LaTeX already knows how to hyphenate words. But it obviously can’t do this for words you’ve invented yourself. Or uncommon words with special characters. For those, you can define how they should be hyphenated yourself.

To do so for every occurrence of the word in the document, use

1\hyphenation{word list}The word list contains your words, separated by spaces, with hyphens between all syllables. Or all points where you allow the word to be broken apart.

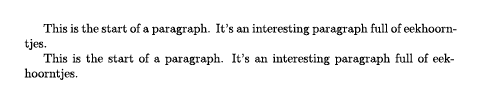

1% Eekhoorntjes is Dutch for small squirrels.

2

3% Latex does a best guess

4This is the start of a paragraph. It's an interesting paragraph full of eekhoorntjes.

5

6\hyphenation{eek-hoorn-tjes}

7% Latex knows how to break it now

8This is the start of a paragraph. It's an interesting paragraph full of eekhoorntjes.

If you only need to perform this on a single word, you can use \-. It inserts a discretionary hyphen: it only displays if needed. (If you know HTML, this is the same as the ­ entity: the soft hyphen.)

If you desperately want to keep several words together, use \mbox{text} or \fbox{text}. They do the same, but the latter draws a box around the content.

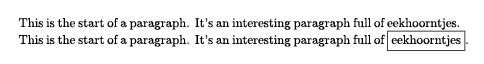

1\hyphenation{eek-hoorn-tjes}

2

3This is the start of a paragraph. It's an interesting paragraph full of \mbox{eekhoorntjes}.

4

5This is the start of a paragraph. It's an interesting paragraph full of \fbox{eekhoorntjes}.

Dashes

Four types of dashes are known to LateX.

| Character | Visual | Description | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

- | - | inter-word | hyphen |

-- | – | (page) range | en-dash |

--- | — | punctuation dash | em-dash |

$-$ | − | minus sign | subtraction operator |

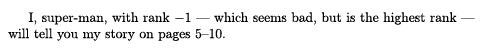

1I, super-man, with rank $-1$ --- which seems bad, but is the highest rank --- will tell you my story on pages 5--10.

You can also produce the en-dash and em-dash with \textendash and \textemdash, respectively.

Word Spacing

By default, LaTeX varies space slightly. For example, it inserts more space after a period that ends a sentence, than one that ends an abbreviation. (E.g. “LaTeX has a lot in common with HTML.”)

If you want to insert a space that can’t be enlarged or shrunk, use ~ (tilde character) instead.

If you want to signal that a period ends a sentence, whatever is in front, use \@ in front of it.

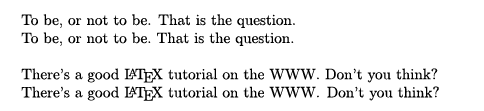

1To be, or not to be. That is the question. \par To be, or not to be.~That is the question. \ \par

2

3There's a good \LaTeX{} tutorial on the WWW. Don't you think? \par There's a good \LaTeX{} tutorial on the WWW\@. Don't you think? \par

To turn off this type of spacing entirely for a certain part of the document, call \frenchspacing there.

Want to support me?

Buy one of my projects. You get something nice, I get something nice.

Donate through a popular platform using the link below.

Simply giving feedback or spreading the word is also worth a lot.