Microphones

Finally, we’re ready for chapters about the nitty-gritty practical details on recording. You understand why things go wrong and the many challenges when it comes to recording. You’ve hopefully arranged your audio chain ( = equipment), room, and song by now—ready to record masterpieces.

So let’s start doing that. First by picking the right microphone. Then, next chapter, by placing the right microphone at the right location.

Recording patterns

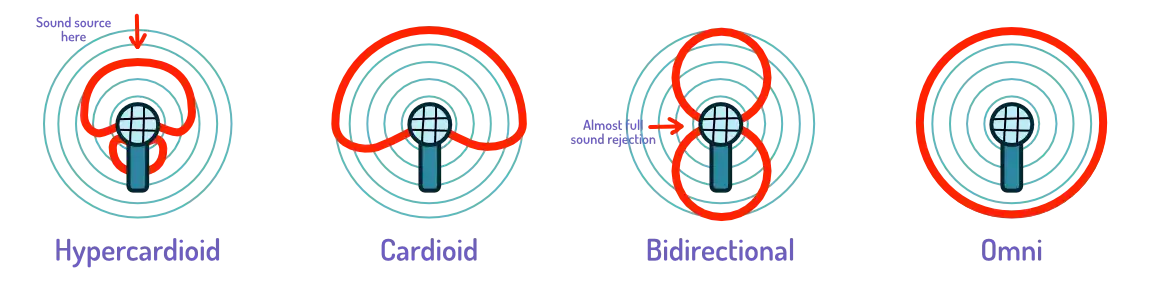

There are four common “pickup patterns” for microphones. These are formally called polar patterns. They tell you in what area the microphone picks up sound.

- Hypercardioid: a tiny blob in front of the mic

- Cardioid: a bigger blob in front of the mic

- Bidirectional (or “figure-eight”): front and back, but absolutely nothing from the sides

- Omni: records equally from all directions

None of them are better or worse than another. You just need to use the right one for the job.

- Hypercardioid is used in live performances or noisy environments. It only records you when you’re very close. This seems ideal, but it forces you to be very mindful about placement. Sing from too far away? You hear nothing. Move your head while singing? The sound changes.

- Cardioid is most common. It’s versatile and works in most situations. A good balance between rejecting sound off-axis, but allowing you to move around without completely disappearing in volume.

- Bidirectional is great for recording two channels or two instruments at once, because the mic records both the front and the back.

- Omni is amazing for recording a group or band, or more a space than a specific person. Phones, laptops, etcetera are all omni.

Some other pickup patterns exist. But they are very rare and mostly slight variations on the “cardioid” type (such as “subcardioid”).

Microphone Types

Knowing the pickup patterns, the common microphone types are easy to learn.

- Dynamic: you see these everywhere, especially on stage. They are hypercardioid, sturdy, portable and usually contain their own pop filter.

- Small Diaphragm Condenser (SDC): also called “pencil mic”. It’s a long stick with a cardioid pattern. Very focused and used on instruments.

- Large Diaphragm Condenser (LDC): also cardioid, but more open. A typical vocal mic, as it captures just a bit more than a pencil mic.

- Ribbon: based on how our ears pick up sound. It’s therefore quite natural and smooth. The consequence is a bidirectional pattern and a more fragile mic.

- Lapel: these are tiny and portable. Also used in movies, tv and theatre—hidden from camera within somebody’s clothes, to pick up only their dialogue. These are usually omni.

There are also multicapsule mics. They allow you to switch or swap capsules, changing the pickup pattern as you want.

This sounds ideal. And yes, it can be very practical. But I wouldn’t recommend it. A “2-in-1” device usually means you get two mediocre things. If one part breaks or malfunctions, you suddenly lost all pickup patterns that belonged to the mic.

Instead, buy microphones that do one thing and one thing well.

Most people start with an LDC. Because of its versatility and its match with the human voice. Extra mics are usually SDC or Dynamic.

Ribbon mics are great, but also expensive and they are noisy. You need a quiet, well-treated environment to use them. They often produce a very low volume.

Why?

Passive vs Active

Mics can be passive or active. Active means that they draw power to amplify their own signal. Passive means they don’t.

SDC, LDC and Dynamic mics are almost always active. They require the phantom power switch to be turned on at your audio interface.

Other mics might be passive, especially ribbon mics. Such passive mics produce a very low volume signal. You’ll probably need a separate preamp (remember that from Equipment II?) to make it usable.

But this comes with a big warning: do not ever apply phantom power to mics that don’t need it. Also, don’t turn phantom power on/off while mics are active.

Although almost all equipment is well-protected against this nowadays—even ribbon mics—I still think it’s good practice. Just good practice in general. Turn all your equipment off before changing things or plugging cables in/out. Be mindful of what buttons you press, of whether phantom power is on or off.

Other buttons

Many microphones come with a few other buttons or sliders. Most likely, they are …

- A volume pad

- A high pass filter

The volume pad reduces the input volume of the mic. Why would you ever want that? Isn’t louder better? Well, yes. But as I’ll explain soon, you can be too loud and then the sound will clip. Some sources, like acoustic drums, are just so loud that you want the mic to tone it down for you.

The high pass filter removes low-end rumble you don’t need. This is produced by appliances, cars passing by, an array of normal sounds during the day. If you hear rumble on your recordings, it’s likely just a pile of low frequencies being picked up and not filtered out.

As such, I recommend picking a mic that has these options. There’s a good reason most have them. You can do both things using other tools (such as an EQ plugin to add that filter). But if the mic automatically does it for you, that means you’ll never forget to do it, and it speeds up your workflow.

No two mics alike

Every mic is different. Not just in pickup pattern or usage, but also in how they respond to sound. Usually, mic manufacturers supply a graph with the “frequency response”. This shows how much the mic picks up certain frequencies.

A “neutral” mic will have a mostly flat line. It responds to all frequencies the same way. (Only the highest and lowest frequencies will drop off or vary. But those aren’t that important.)

The more expensive you go, the more you can achieve this.

But … is that really what you want? I’d say no. At least, not always.

You want microphones that provide a certain color or texture to what you record. Once you have a small set of such microphones, you can pick the best candidate for each sound source. The microphone won’t just be a neutral bystander, it will color and enhance the sound automatically.

When picking your first microphone—with no budget for more—yes, go for neutral. As neutral as possible. So that it doesn’t make any source sound worse or unusable.

But after that, when building your collection, go for variety and color. Picking the right mic for a recording can save you 90% of work (and issues) later.

I, therefore, think it’s best to shop audio equipment in a real store. Not online. Not through recorded samples. (They’ll sound different on every device anyway, and you can’t be sure they haven’t edited that.) Go on a journey through all the mics they have. Listen to how they color sound. Pick the one you like the best.

Matching pairs

I don’t just recommend varied mics for their color or mood that they add. It’s also for that stereo image.

If you record something with multiple microphones that are identical (a “matching stereo pair”), you’re far more likely to run into phasing issues.

Because they are the same microphone! They’ll respond to the sound in the same way. Their output will be nearly identical. It will be hard to avoid phasing issues.

But if the mics are different? They’ll “hear” the same sound in a different way. They’ll automatically be different, no matter how you place them, circumventing most phasing issues.

I don’t have two mics of the same type. All my songs use different mics for stereo recordings. It’s perfectly doable and I’d recommend it.

Conclusion

Now you should have a good idea about which microphones are out there. Hopefully you have a few in your possession, because we can now talk about how to use them!

Want to support me?

Buy one of my projects. You get something nice, I get something nice.

Donate through a popular platform using the link below.

Simply giving feedback or spreading the word is also worth a lot.