The definition of story

Okay, so you have an idea, and you’ve answered the questions from the first chapter (about why you’re writing it). Now what? Now we try to formulate that idea according to the definition of how a story is constructed.

What is a story?

Most of the writing world agrees on the following idea. Like most, I started out as a rebel who thought that “the rules don’t apply to me”. Now that I’ve written tons of stories, I know stories only get better the more strictly you adhere to this system.

A story is …

- A character with a goal

- Encountering obstacles on the way towards reaching it

That’s it.

Why would this be fun and interesting to humans? Isn’t it annoying if somebody wants something, and they just can’t get? Why have we made a business out of inventing obstacles and problems?

Because when two opposing forces meet—they want to reach a goal, an obstacle prevents that—you get conflict. And humans love conflict.

Throughout this course, I’ll call the main character of a story the “hero”. It’s short and makes sense in almost any story. Alternatives are the shorthand MC or protagonist.

Conflict

The why

Why, though? Why do humans love conflict? Two reasons.

- Humans enjoy tension and release. Conflict builds tension, tension, tension. As such, it’s only fun if it’s also released at some point.

- Conflict presents a question: how will this be resolved? Which side will win? These are interesting questions begging for answers.

In a way, a conflict is just a mystery, something that keeps people engaged because they want to know the answer to that mystery. But it’s an enhanced mystery: you also get the tension, the character development, and everything else.

The how

Many equate conflict with problems. They invent some annoying obstacle, or random setback, or argument between friends, and think “hey, this is conflict, this is an amazing story!”

I sometimes read and critique novels from amateur writers. The “stand in a circle and argue”-problem is a common one. They write many, many scenes about people just arguing about something, treading water, inventing minor annoyances and never resolving any of it. I did the same thing in my first stories.

This is obviously not true. Only a small set of problems is actually interesting conflict suitable for a story.

This is my definition.

- Clashing Goals: It’s a clash between a character’s goal and an obstacle, preferably created by another character. (It’s not just any “issue”. Yes, it’s annoying if you can’t find a series to watch on Netflix after searching for an hour, but is that interesting conflict for a novel?)

- Urgent: The characters must act now. There’s a clear time limit or incentive to be as active as possible.

- Loss: It’s not enough for the protagonist to achieve some nice bonus if they win. They must lose something, with certainty, if they don’t win. That is a much stronger conflict, as humans are naturally risk averse. (We care more about potentially losing a friend, than making a new one.)

It’s nice if a conflict is big or strong enough to be sustained over the whole book. (Or even a whole book series!) It is very common, though, to change the conflict as time goes on. One problem might be resolved, but leads to a new one.

Further reading

This is an overview about the “core” of storytelling. Enough to get you started and to test if your story is working.

However, everything about plot and conflict is discussed in greater detail in my course on Plot.

Character

There are countless good stories in which the character fights obstacles that are not other characters. Maybe they live in an environment that’s especially dangerous. Maybe they just want to achieve something that’s hard to do, even without anybody actively working against you, like becoming a professional athlete.

In most case, though, they still “humanize” this opponent. That hazardous environment? Yeah, designed by some malicious corporation. You need to train hard to become a professional athlete? Yeah, bad luck, your coach is also a mean human being favoring another pupil.

This is also apparent in our language. All our sentences need a subject and a verb. Our language is designed in such a way that everything must be done by someone! Even if that isn’t the case. We say “it rains” or “it’s cloudy”, not just “rain” or “rain falls”.

Conflict between multiple characters is just more interesting than anything else. It means the other side—the “obstacle”—can also do smart moves or see character growth. It’s more realistic and offers more opportunity for moral questions and gray area. (The biggest obstacles in our lives come from other people, not inanimate objects somehow creating huge issues.)

That’s why I’d recommend picking conflicts between characters, when in doubt.

What is a character?

Again, we ask why we need a character. Why people would follow one.

In all my research and experiments, I’ve only found two solid reasons.

Relatable: people like seeing characters that somehow relate to them or their daily life. They feel connected, they feel recognized or accepted. (One of the biggest fears of humans, in general, is to be misunderstood or completely cast out of all social groups. Reading about a group where you just might belong is therefore satisfying.)

The hero: this refers to what we talked about last chapter. Stories are about extraordinary people and events. People love seeing a character achieve something, despite flaws, obstacles, or mistakes. It is inspiring. If the hero can do it, then maybe, just maybe, they can achieve something extraordinary in their own life as well.

That’s why I do not agree with the current trend in films to make heroes stupid and incapable as a “surprise” or as a way to “humanize” them. Yes, make heroes flawed and relatable. But stories need a hero who achieves something that’s worth telling a story about. An ideal, glory, something to strive for.

Knowing this, what makes a character?

- They have something they desperately want (their goal)

- There is something else they actually need (their lesson to learn, their growth, their progression)

- They have clear flaws and limitations.

- But, despite that, will do some extraordinary thing at some point in the story.

People are flawed. We connect with characters more through what they also struggle with (just like us), rather than the skills they also have (just like us). And limitations are, generally, more interesting.

Their “want” makes the story possible. It provides the first conflict and the first Element of Storywhy: the framework for entertainment, action, mysteries.

Their “need” (and limitations) provides the other two Elements of Storywhy: a moral lesson / deeper meaning, and growth.

Further reading

Again, this is just a quick practical summary. For more detail and tips, visit my course on Character.

Combining all of this

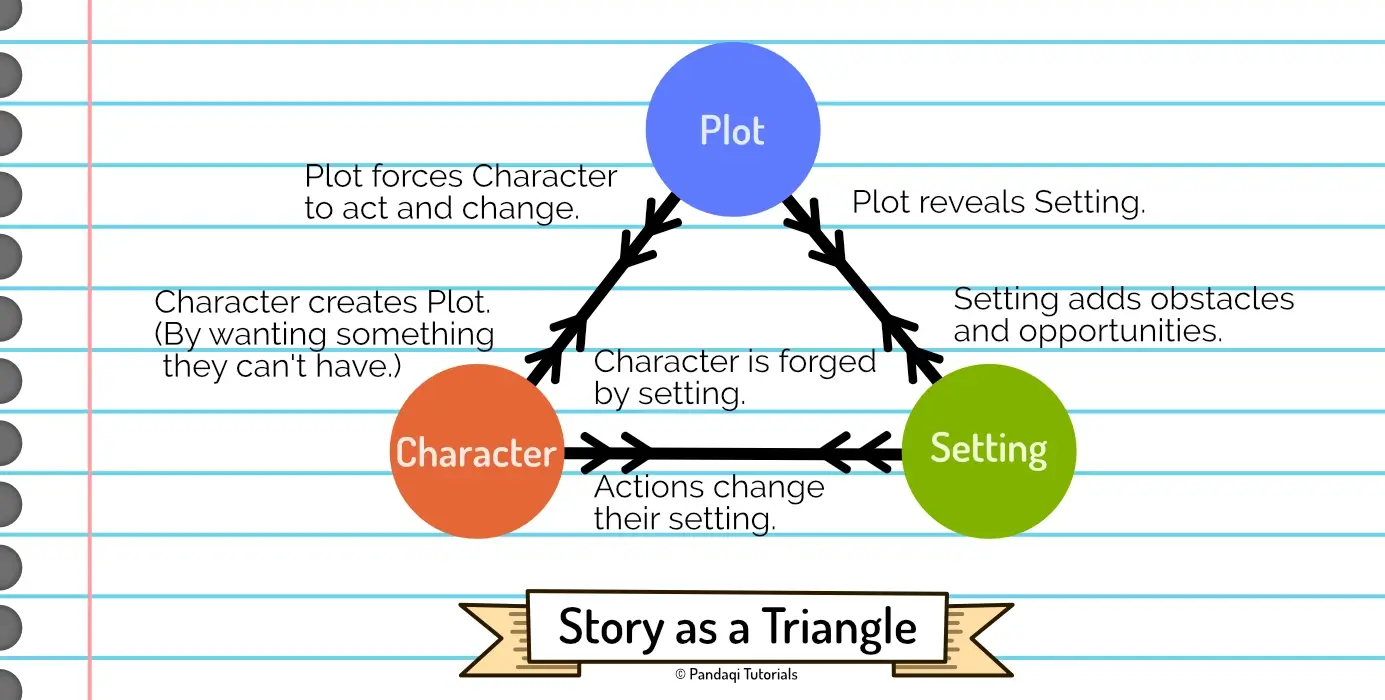

I’ve just explained to you the importance of Character, Plot (created by the character), and Setting (the situation or world that allows the story to happen).

Unsurprisingly, those are seen as the Three Core Elements of Story. They cannot exist without each other, and influence each other all the time.

Notice that this is different from my Three Elements of Storywhy. Those are about why we tell stories and why we’d be entertained by them. The elements above, from the triangle, are the practical tools we have for how to tell those stories.

Once you’re done with this course, I highly recommend you read the specialized (more in-depth) courses about each of these three components:

- Plot

- Character

- Worldbuilding (which is the common term used for setting, especially in speculative fiction)

Conclusion

So, how do you start a story? You invent a first chapter that …

- Introduces your protagonist: a hint at their flaws, their need, their personality. (We only care about a story because we care about the characters within it.)

- Introduces their goal (their “want”).

- And an obstacle that prevents them from getting it. Preferably one that provides good conflict: a clash of goals with a formidable opponent, urgent and with certain loss.

The first chapter builds towards that conflict. In other words, the goal and obstacle only clash at the end of the first chapter. If you’ve set it up well, the rest of the novel will be much easier from now on.

Remember my comment about adhering to this formula rather strictly? I say that because many writers tend to overdo it. They give their protagonist multiple goals. They introduce multiple conflicts. They create an obstacle that provides a lot of action and mystery, but isn’t urgent, and therefore falls apart after one chapter.

Don’t do that! (I’m very guilty of this myself, though, so I understand.) Stick to this idea, because it is the core of what makes a story … a story. This is usually not the part where you take creative liberties.

It would be like taking away the screen for a video game. Or removing half the frequency spectrum when playing back music. At some point, you lose the elements that define the thing.

No, the creativity kicks in while writing the rest of the story. So let’s talk about that now.

I also like this funny explanation of story (by John Roger) that summarizes all this: “Who wants What? Why can’t they get it? Why do I give a shit?”

Want to support me?

Buy one of my projects. You get something nice, I get something nice.

Donate through a popular platform using the link below.

Simply giving feedback or spreading the word is also worth a lot.