What is plot?

For most people, the definition of plot is simply “the things that happen”. And, honestly, you don’t need much more than that. It’s completely true: everything that happens in your novel, is called plot (development). I see no reason to get extremely theoretical or precise.

The big trick, however, is what happens. We all know a good plot from a bad one. A plot that feels tense and exciting, versus one with meaningless action that feels like it’s standing still. Both of them have stuff that happens, so what makes one good and one bad?

Throughout this course, I’ll refer to the main character of your story as “hero”. It’s short, simple, and fits well.

Cycle of Consequences

My definition of plot, which I’ve found the most helpful after years of writing, is that plot is a cycle of consequences.

Plot is not just a sequence of events, unrelated or only vaguely related. It is a chain of related events.

Plot is not a news article, which merely states the one thing that happened. (Nor is it a newspaper, with many completely unrelated events.)

Plot is a cycle of event and consequence, of action and reaction

The cycle has to start with some event. We call this the inciting incident, which happens as soon as possible. Pick it well, and your plot flows easily. Pick it badly, and it might be impossible to rescue the plot.

From that moment, however, the cycle should just continue and continue. Whenever something happens in your plot, it should either be an action (to achieve some goal), or a reaction (to previous actions). If it’s none of these, it doesn’t belong in the plot!

Until, finally, the cycle stops because no more action or reaction is needed. The characters are satisfied with the current state or are incapable of changing it. (Many stories end with the “bad guy” dead, imprisoned, or without power.) That’s the resolution, which happens at the end.

This might sound harsh (or very obvious), but this is easily forgotten in the complexity of storytelling. People have this really great character they really want to use … so they shove the plot around to fit the character. But in doing so, they broke the chain, and now parts of the plot feel “useless”, “slow” or “illogical” because they broke the cycle.

Similarly, many stories (especially blockbuster movies) build up towards awesome action. A fight scene, a murder, an escape, something cool. But when that’s done? They completely ignore the consequences. They only wanted the action, not the reaction. That’s not a plot. It feels unsatisfying and unrealistic.

In the case of blockbuster movies, the general feeling from every viewer is: “yeah, it was fun while watching, but afterwards it just felt hollow”

The ideal plot is …

- One with completely logical (perhaps obvious) actions and reactions

- Which still isn’t predictable or boring

A bad example

Your hero gets fired from their job. They don’t care, because they were already preparing for their dream job anyway. (Bad because this makes the firing meaningless, as it prompts no reaction.)

They continue preparing like nothing’s happened. At some random moment, they decide to apply. (Bad because it’s not a reaction to anything, or a conscious action with reasoning behind it.)

They get turned down. They decide to move to Hawaii and pursue something else entirely. (Bad because this is no logical consequence. Certainly not one that the reader could have foreseen.)

They suddenly receive a large bag of money. They do nothing with it (for a while) :p

Yes, these are really bad examples. They’re just events with no logical connection, or no reaction. But I wanted to establish a baseline intuition about what plot is. (And even then, many stories get this mixed up.)

A good example

Let’s say your story starts with your hero getting fired (from their job). This action is the inciting incident.

To build a plot, you simply ask yourself about the reaction. What’s the consequence? Maybe their previous job was safe but boring. Now that they’re fired, they finally apply to that dream job they always wanted.

But that dream job requires intensive training. Conflict! They have to spend all their money to get into some expensive program.

What’s the consequence of that? Maybe the hero has a partner, and they were saving up for something big, and now all the money’s gone. Conflict!

What’s the consequence of that? His partner becomes less and less supportive, making the hero doubt if it was even a good idea to pursue his dream job.

What’s the consequence of that? Keep asking that question, and you get a plot.

A framework for story

The approach above is about what plot is. I think it’s useful to apply a different approach to define the purpose of plot.

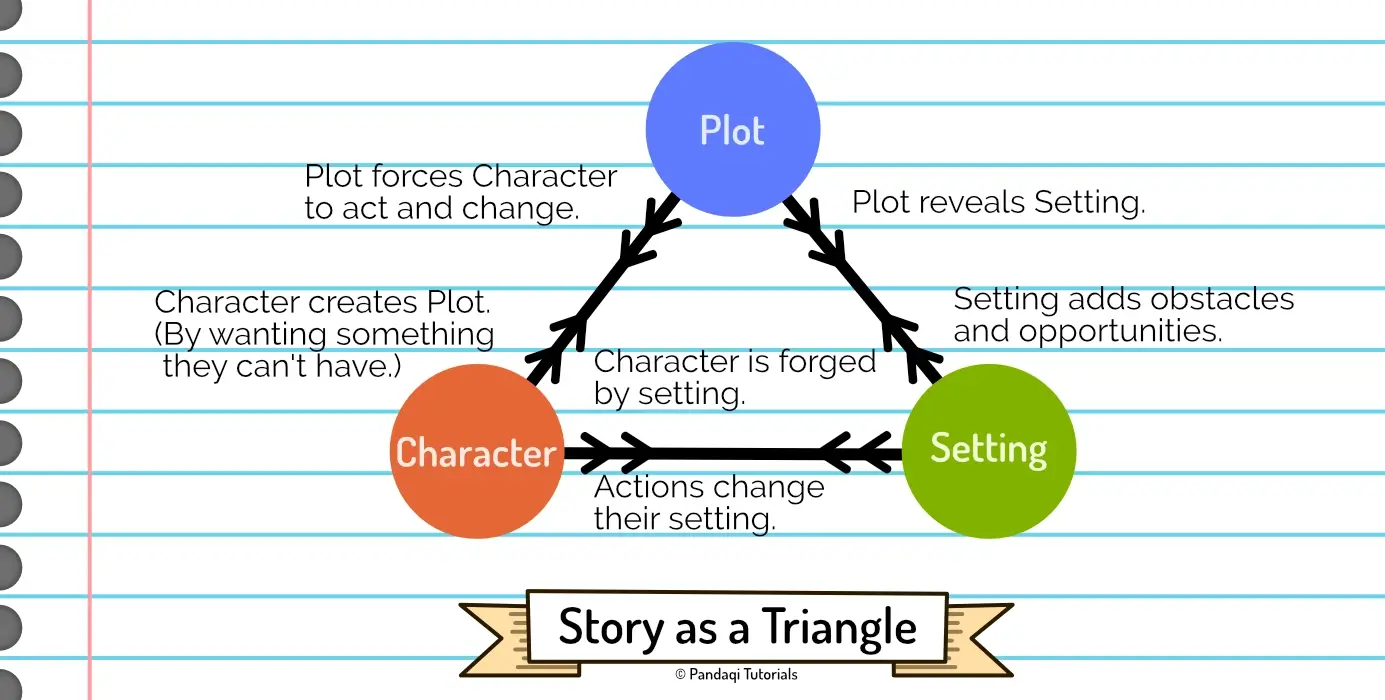

Most people ascribe to the Triangle of Storytelling: Plot, Character and Setting.

It’s a triangle because every element needs the other two elements. Plot is merely a framework to reveal character and setting. On its own, it’s meaningless. It’s made-up actions, decisions and fights. But the plot allows great characters to shine and a world to come alive. The plot allows you to write funny jokes, interesting scenes or engaging mysteries.

As such, always ask yourself

- How can I construct the plot to show our character(s) the best?

- How can I construct the plot to show the setting/theme/world the best?

A plot that doesn’t serve character or setting, is a plot without purpose.

In general, it’s advised to be really tough on your characters. Design the plot to test and challenge them at every point, as much as possible. This is how you “get the most out of your hero”. It should feel like the plot was a game designed specifically for them.

The same is true for setting, although you’ve probably noticed that it’s often rated as the least important. (Character first, then plot, then setting.) Find a plot that showcases your unique setting. If your novel is set in some other time period, create a plot that only works in that time period. A plot that really shows the good and the bad.

Similarly, if your novel is set in a fantasy world you invented, create a plot that ensures we get to see the most interesting parts of that world! Design the plot to send your hero to interesting locations. Design the plot to make your hero bash their head against stupid laws or customs in your world.

If you do that, you’ve fulfilled the purpose of plot. And you probably already assumed that a plot with purpose is much better than one without it.

This can also help with mindset and motivation. I’ve often looked at the plot of my novel and thought: “What am I doing? These are just made-up events, why would anyone read this?” The purpose of plot isn’t to be interesting. It’s to be a framework that allows interesting stuff to happen.

An example

Let’s say your hero is very selfish. Then design a setting that punishes selfishness severely. Maybe it’s a fantasy society that rewards people if they help others and punishes people who flee from disaster (by death). And then you design the plot to show this character trait: you start the story with the hero running away from a house on fire, instead of helping.

A fight scene, on its own, is terribly uninteresting. It becomes interesting if we care about the characters involved. If it makes creative use of the setting or the surroundings. If we care about the consequences of who wins the fight. As such, to make an action scene better, you don’t have to “write it better” or “add more flashy stunts” or “add explosions!”. You have to design a better framework—a better plot—to which you can glue the action scene.

Similarly, the reveal of a mystery, on its own, isn’t great. It’s just a bit of information, told to the reader. You make it great, however, if you construct the whole plot around it. If the revelation of that mystery matters to your characters. If you time the reveal to be at the absolute worst moment for your hero. If you invent a plot that allows showing the reveal, instead of literally telling it.

This is one of the true skills of writers, in my opinion. The intuition to come up with the perfect plot to make the characters and setting shine. To come up with smart plots that naturally lead to funny scenes or great reveals.

What if I don’t like planning?

In general, there are two types of writers: planners and pantsers. Planners want to know their whole story ahead of time, and then simply write it. Pantsers invent an interesting start, and then make it up as they go along. (Most people fall somewhere in between, instead of at one extreme.)

The tools taught in this course will help both types. Planners merely use it before writing, when creating the outline. Pantsers use the tools while writing, or to fix things afterwards.

I myself am clearly a pantser. But … I still plan and outline. After years of writing, I’ve learnt the balance between how much structure and how much freedom I need.

In fact, true pantsers don’t exist. After writing a few stories, you’ve already learned rules and principles about plotting, which you will subconsciously apply. So, even if you “make up the story by the seat of your pants”, your head is still outlining and planning ahead.

That’s why I recommend outlining for all writers. You simply have to do it in a way that suits you and your writing style. to the extent that it helps you.

Why? Because outlining allows you to offload work, which you’d otherwise have do while writing, to a separate brainstorm session. You don’t need to think of a bazillion things while writing, because you’ve laid down major story moments beforehand. You don’t need to keep your whole fantasy world in your head while writing, because you’ve already determined which parts matter most beforehand.

Our brains are a messy, fallible mess. Whenever possible, write stuff down, and offload work to different moments. This prevents you from being blocked or overwhelmed while writing, even if you’re a pantser like me.

In this course, you’ll also learn many “plot archetypes”. These are common plots that you see everywhere, such as a “master-apprentice plot” (with two characters, a master teaching some skill to their apprentice) or a “fetch quest” (a group of characters travel and fight to get some magical objects).

Merely writing down which plot archetype you want to use, beforehand, clears so much space in your head. It gives you a handhold at all times, without actually limiting you. There are still infinite (creative) ways to implement a master-apprentice plot, for example.

Conclusion

This was a very broad definition of plot and how to use it. Any “method” or “structure” you can find, about writing, will stay true to this. If you keep this in mind, I think you will never create a terrible plot. The flipside is that this isn’t very practical and doesn’t say anything about the nitty-gritty details of plotting.

That’s why the next chapter provides a slightly more narrow idea of plot. After that, I’ll dive a bit deeper into each element (such as that inciting incident). And then we’re off to the practical plotting tools and you can start writing!

Want to support me?

Buy one of my projects. You get something nice, I get something nice.

Donate through a popular platform using the link below.

Simply giving feedback or spreading the word is also worth a lot.