Text II

The previous chapter introduced many basic ways to manipulate how text is displayed on your website. I glossed over one major change, however, which is … the actual font!

Why did I gloss over that? Because it requires a bit more explanation and I wanted to push that to its own chapter.

Font Family

To set a new font, use the font-family property. It allows a list of fonts, separated by a comma (,).

Why a list? It tries all the fonts, from left to right, until it finds one that successfully displays. In other words, fonts later on the list are a fallback. (Because the worst thing that can happen, is no text or all text in an ugly font you didn’t choose.)

How could a font fail to display? Because by default, CSS relies on fonts being installed (on the user’s device). If you say font-family: Calibri;, it will only display if the user has the font Calibri installed.

Obviously, you can’t rely on that. There’s only a tiny list of fonts that you can reasonably assume are installed everywhere. (Those are Arial, Georgia, Times New Roman, Helvetica, and Courier.)

To reduce this problem, CSS does provide its own fallback fonts for five different categories: serif, sans-serif, monospace (computer), cursive (handwriting), and fantasy (decorative). One such category is usually typed at the end of the font list, to ensure it at least has a proper fallback.

In this example, Garamond is my preferred font, but not everyone has that installed. Also notice how fonts with spaces in their name need to be put between quotes (").

If you know some fun fonts on your system, try them in the example and see if they display!

By the way, I just love the fact that the developers behind CSS actually went for “fantasy” as the keyword for decorative and playful fonts.

Custom Fonts

The real solution to the problem, of course, is to actually load the custom fonts your website uses.

To load one version of a font, use the @font-face {} rule. Inside, two properties are required.

font-family: the name of the font (pick whatever you want)src: an URL pointing to the font file. (Or a list of URLs to different versions of it, separated by a comma.)

This downloads the font at the URL, then saves it under the name you gave it. From now on, you can use the name and be certain that the user has it.

Font files can be large. So large, in fact, that new extensions were developed simply to allow fonts to become smaller and download faster. These are the woff and woff2 extension. You want to use font files in that format, if possible.

Also within this @font-face rule, you can set the other properties of this file. The ones we discussed in the previous chapter: font-weight, font-style, and font-stretch.

The example below loads the bold version of a custom font.

Finally, it’s recommended to always set an extra property here: font-display: swap;

What does this mean? It means the webpage already loads using your fallback font, while it still downloads the custom font. Once the download is complete, it automatically swaps the fonts and the webpage is now done.

This prevents having to “wait” on (large) font files to load, displaying an empty (or incorrect) webpage in the meantime. There’s basically no reason not to add this.

Common Questions

Where do I get font files? There are numerous websites with (free) downloadable fonts. Probably the best resource, though, is Google Fonts.

It also allows you to merely link to the fonts on Google’s server. This saves you bandwidth and storage space, and can be faster to setup for beginners. Ultimately, though, you don’t want your website to depend on other websites too much. Over time, I have come to prefer downloading fonts and keeping them on my own server.

For all this, follow the simple instructions on their website.

How do I convert font files? I like to use Transfonter. It not only converts files, it also provides a stylesheet with the correct @font-face rule (and some other features).

Whitespace

When you learned HTML, you probably learned that it collapses whitespace. No matter how many spaces or newlines you add, it all gets collapsed into just one single space.

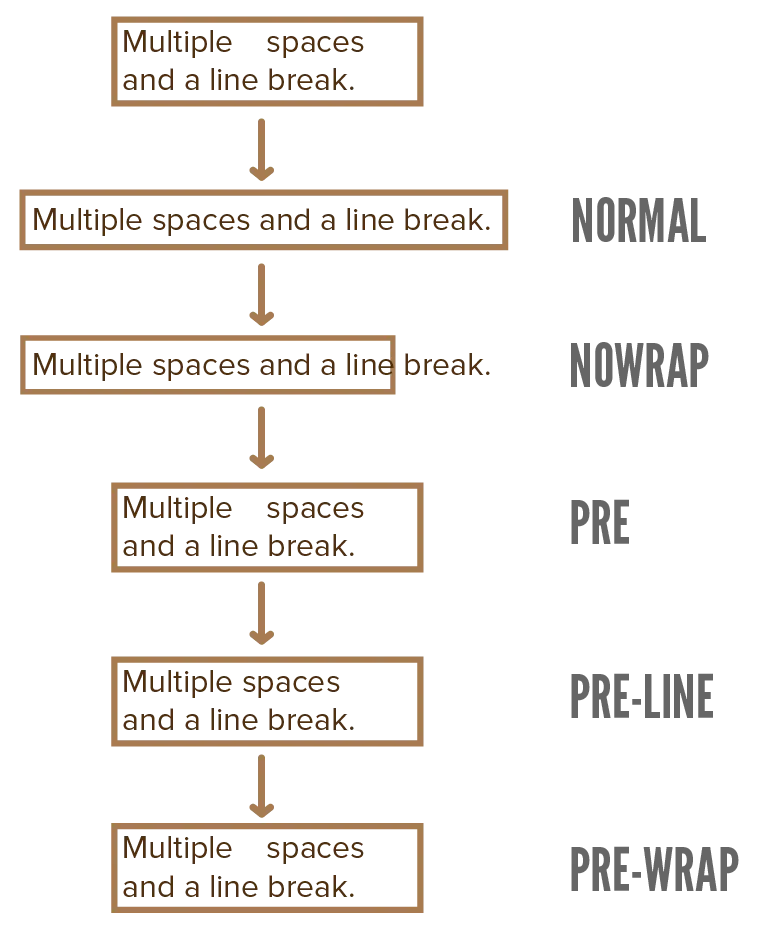

What if you want to change that? Then you set the property white-space to one of the following properties: normal, nowrap, pre, pre-line, or pre-wrap. The image illustrates how each of these work.

As you see, nowrap just completely disables text wrapping.

The pre setting preserves the whitespace you entered. The pre-line only preserves newlines, not regular spaces. The pre-wrap does the same, but allows wrapping.

In the example, check the HTML tab to see the original whitespace in the input.

Wrapping

By default, words are never broken in two. If a word doesn’t fit on the current line, it’s moved to the next line in its entirety.

Two issues can arise, however.

Issue 1: what if a word is so long that it doesn’t even fit on one line on its own? In that case, use the overflow-wrap property.

- Set it to

anywhereto allow breaking that word, well, anywhere. - Set it to

break-wordto prefer breaking it at sensible places (which is vaguely defined, to be honest).

Issue 2: what if I have a design where it just looks ugly to keep words together? (For example, you have a text box with a really tiny width, which means you have lots of lines containing only one word.) Then you can set the word-break property to break-word. (Yes, the same thing, but reversed.)

In the example, play with the paragraph width to see how words break. Also turn these properties off and see how text overflows.

Hyphenation

Breaking words in two is usually only done in books, and not recommended on websites. In books they add something else to help the reader understand this break: hyphens.

Those can be turned on in CSS as well with the hyphens: auto; rule.

This requires a language to be set on the element, using the lang attribute. Otherwise the browser doesn’t know what dictionary to use for intelligently breaking words in two!

This property is supported everywhere, but not every language is supported. (Those dictionaries would bloat the file size of browsers immensely.) The only language you can trust to be supported is, of course, English.

In the example, you might need to resize the width of the paragraph to make sure a few hyphens appear. This depends on your screen size!

Conclusion

That concludes our chapters on text, for now. There are a few more properties, but they’re more decorative or easier to explain when connected to another topic.

Let’s continue to the next chapter, which will explain another major way to spice up your designs. (As well as a new general rule of CSS that will be useful to know from now on.)

Want to support me?

Buy one of my projects. You get something nice, I get something nice.

Donate through a popular platform using the link below.

Simply giving feedback or spreading the word is also worth a lot.